Biting into a piece of tandoori chicken should feel like a small festival in your mouth—fiery, smoky, and bursting with juice. But there’s that all-too-familiar moment when you sink your teeth in and... nothing. Just dry, stringy chicken that’s desperately holding onto its past life as something delicious. Why does this happen? It’s tempting to blame the recipe or just think homemade is never as good as that unforgettable takeaway from Little India down the street, but the culprit isn’t that mysterious.

The Science of Tandoori: Why Does It Get So Dry?

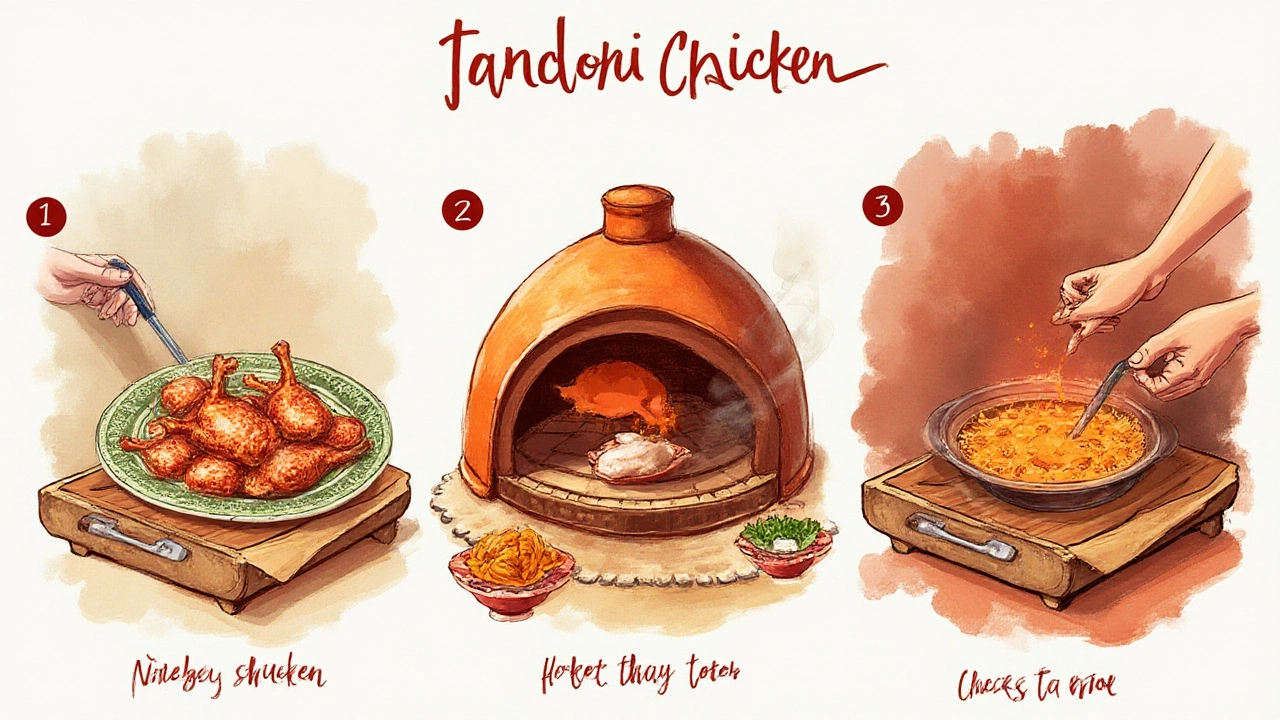

If you’ve ever made tandoori chicken at home, I bet you’ve had at least one attempt where the result was as parched as a desert in Rajasthan. The major reason for dry tandoori chicken starts and ends with the protein itself. Chicken, especially breast meat, has very little natural fat. Without enough fat, there’s nothing to buffer the intense heat of a tandoor (or even your oven) from zapping all the moisture out within minutes. Even if you use thighs or drumsticks, high heat without the right prep can leave them leathery.

The traditional clay tandoor is an absolute beast. It burns way hotter than a home oven or grill ever could, sealing moisture inside the chicken within seconds. When we use a standard kitchen setup, the heat isn’t intense enough or surrounds the chicken evenly. So, the outer layer dries long before the inside catches up. Home cooks think longer cooking ensures safety, but overcooking destroys those precious juices.

Here’s the funny part—people often believe that marinating the chicken for days guarantees juicy meat. But acids from yogurt and lemon juice actually start to cure the chicken, almost like a ceviche. If you leave it too long, the fibers break down so much they can’t hold onto moisture under heat. What you end up with is a fibrous, dry bite—definitely not the tandoori dream.

Then there’s the spicing. Many home cooks are tempted to skimp on oil in the marinade, thinking less fat means healthier chicken. But fat doesn’t just add flavor; it creates a barrier to help lock in juice. It’s like sending your chicken onto a battlefield without armor—one intense blast and it’s lost.

Ever thought about the chicken itself? The fresher the bird, the juicier your final product will be. Supermarket chicken, that’s been plucked, packed, traveled, and shelved, often ends up a little dehydrated even before you marinate it. Some of us in Bristol, including myself, have noticed the difference between butcher-fresh chicken and supermarket packs—even Ginger, my cat, can sense which leftovers to beg for.

Techniques That Make or Break Moisture

The method you use to cook tandoori chicken matters more than you’d think. When I first tried making it at home, I loaded up on all the classic spices—garam masala, Kashmiri chili, cumin. The flavors were spot on, but the meat was as dry as my British humor. So, I started experimenting with everything from different pans to overnight yogurts, and here’s what I found.

Let’s talk about marination. The golden window is 6 to 8 hours. Longer, and you risk mushy, stringy meat. Shorter, and the flavors don’t permeate. Always add a generous glug of oil—mustard or even a flavorless vegetable oil. Ghee, if you’re adventurous, adds a rich, slightly nutty finish. The fat not only traps moisture but also helps in crisping the outer layer beautifully when heated.

Don’t skip the salt. Salt is a little magician; it changes the structure of the meat, helping it hold onto water as it cooks. Too little and your chicken doesn’t brine, too much and it starts to break down. Aim for about one teaspoon per pound, distributed evenly through the marinade.

Now onto cooking temps. If you’re using an oven, crank it up high—about 475°F (245°C). Use a rack so hot air circulates around the chicken. If you grill, let those coals burn until they’re white-hot before slapping on the chicken. Don’t forget: the chicken has to go in straight out of the fridge. Room temperature chicken loses too much moisture while slowly coming to oven temp; cold meat retains juices longer and cooks more evenly.

Basting isn’t just a chef’s trick for show. Brushing the chicken with melted butter or marinade during cooking gives you a double whammy—moisture on the inside, and a shiny finish on the outside. Try mixing a bit of kasuri methi (dried fenugreek leaves) in your basting sauce for that authentic, smoky aroma. I swear, every time I do this, Arjun thinks I’ve snuck out and smuggled home restaurant takeout.

You know what’s also overlooked? Resting. When you pull the chicken from the oven or grill, resist the urge to tear into it right away. Let it sit for five minutes, tented loosely in foil. This short pause lets the juices redistribute—slice too soon, and you’ll watch all that hard-earned moisture bleed out onto the plate.

A thermometer is your best friend here. Tandoori chicken should hit 165°F (74°C) at the thickest part. This isn’t just food safety protocol, it means the proteins have set, locking in moisture. Go over, even by ten degrees, and you risk dry meat.

If you’re worried about getting that deep smoky taste at home, there’s a trick called dhungar. Heat a small piece of charcoal till red-hot, put it in a small bowl in the center of your cooked chicken, then add a few drops of ghee and trap the smoke with a lid for a few minutes. No one will believe this came out of a regular kitchen.

Game-Changing Tips for Juicy, Tender Tandoori Chicken

Here’s where things get practical. Start with skinless, bone-in chicken legs or thighs. The bone insulates the meat slightly so it cooks more evenly, and dark meat has more fat to keep everything tender. If you must use breast meat (maybe you like to live dangerously), cut each breast into two thinner fillets. This way, everything cooks more quickly and loses less juice.

Don’t drown your chicken in yogurt. More than half a cup per pound means you’re just steaming the meat in goo. The idea is to lightly coat every surface, not soak the chicken until it loses its identity. For a real punch of flavor, use hung curd or Greek yogurt—the thicker, the better. This sticks close to the meat and creates a nice charred crust when exposed to high heat.

Spices do more than just flavor. Try mixing a pinch of corn flour or chickpea flour into your marinade. It’s a chef’s hack: these act as moisture-locking agents and help create that signature crusty exterior, just like at your favorite Indian restaurant.

Watch your cook times. In a super-hot oven with convection, drumsticks and thighs rarely need more than 25 minutes. Flip halfway, baste twice. On a grill, cover to create a mini-oven effect and hold in heat, but check regularly to avoid blackening—burnt isn’t authentic.

If you’re bold, brine your chicken first with a simple solution of salt and a bit of sugar before marinating. This guarantees juicier results and lets you get away with cooking at higher temps. But if you do, halve the marinade salt or things get too salty, too quickly.

Serving hot is non-negotiable here. Cold tandoori dries fast, and reheating in a microwave is a fast track to shoe-leather chewiness. If you need to make extra or serve later, reheat in a covered pan with a splash of water or butter, just enough to gently steam the chicken back to life.

Even the atmosphere makes a difference. Honest. In Bristol, our damp English air means my chicken doesn’t dry out as quickly as when I tried this in Jaipur’s hot summers years back. High ambient moisture = juicier chicken, who knew?

Pair with cooling chutneys—mint, yogurt, even a quick cucumber raita. The freshness actually tricks your palate, making juicy chicken taste even juicier. If all else fails, save any leftover dry bits. Chop them and use in salads or toss with butter for a quick tandoori stir-fry. Ginger, my cat, doesn’t mind dry but I doubt you want to share your hard-won chicken with pets.

So next time you’re wondering why your tandoori chicken is drier than the British Museum’s mummy display, just remember: it’s a mix of heat management, marinade science, and care before and after cooking. Tandoori chicken can be so juicy you won’t care about the sauce—if you play your cards right.