Indian Sweets Comparison Tool

Comparison Results

How and differ in traditional preparation and cultural significance

Key Features

Key Features

Regional Significance

Regional Significance

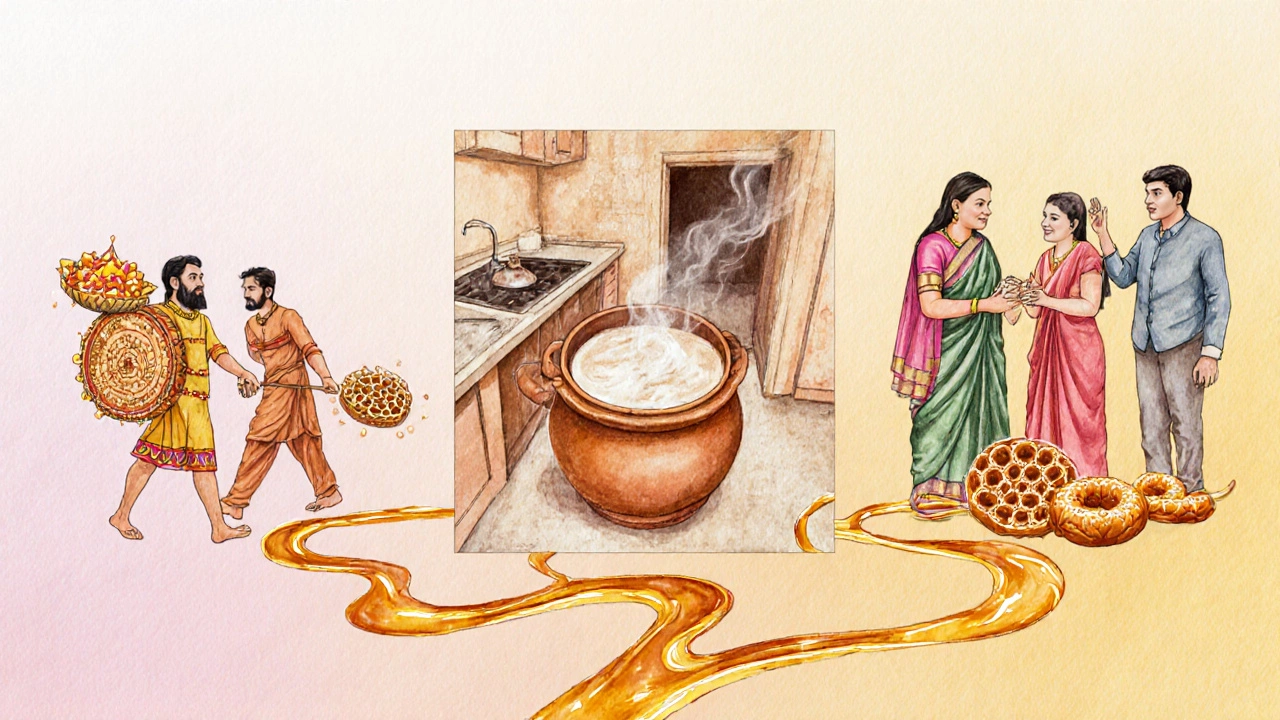

Ask someone what the traditional sweet of India is, and you’ll get a dozen answers. That’s because India doesn’t have one single traditional sweet-it has dozens, each tied to a region, a festival, a family recipe passed down for generations. There’s no official national dessert, but if you had to pick the most widely loved, most deeply rooted, and most unmistakably Indian sweet, it would be jalebi. Crunchy on the outside, syrup-soaked on the inside, and bright orange from saffron or food coloring, jalebi is sold on street corners from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, eaten during Diwali, Eid, and weddings, and even served in royal kitchens centuries ago.

Why Jalebi Stands Out as the Most Traditional

Jalebi isn’t just popular-it’s ancient. Its roots trace back to the Persian zulbiya, brought to India by traders and invaders during the Mughal era. By the 16th century, Indian cooks had adapted it, using fermented batter made from gram flour instead of wheat, and frying it in hot oil into spirals before dunking it in sugar syrup. That simple change made it uniquely Indian: the batter ferments naturally, the syrup is often flavored with cardamom or rose water, and the texture-crisp yet tender-is unlike anything else.

Walk into any Indian sweet shop in Delhi, Varanasi, or even a small town in Odisha, and you’ll see jalebi stacked in metal trays, glistening under the lights. It’s served hot, often with a dollop of thick, chilled rabri (reduced milk), making it a dessert that balances warmth and coolness, sweetness and richness. Unlike many sweets that require special occasions, jalebi is eaten year-round. Kids buy it after school. Couples share it on dates. Farmers eat it after a long day in the fields.

Other Major Traditional Sweets Across India

While jalebi is the most widespread, other sweets are just as important in their own regions. In West Bengal and Bangladesh, rasgulla reigns supreme. These soft, spongy cheese balls, made from chhena (fresh curd cheese) and cooked in light sugar syrup, were invented in the 19th century by a confectioner in Odisha but became a Bengali icon. The secret? The syrup isn’t thick-it’s watery enough that the balls absorb it fully, swelling to twice their size. A good rasgulla should bounce slightly when pressed and melt in your mouth.

In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, gulab jamun is the star. Made from khoya (milk solids), fried until golden, then soaked in rose-scented syrup, gulab jamun is richer and denser than rasgulla. It’s often served warm during Diwali and weddings. Some families add a pinch of cardamom to the syrup; others fry the balls in ghee instead of oil for deeper flavor.

Down south, in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, payasam (or kheer) is the go-to dessert. Made with rice, lentils, or vermicelli, slow-cooked in milk with jaggery or sugar, and flavored with cardamom, nuts, and saffron, payasam is served at temple offerings and family gatherings. It’s not flashy, but its simplicity is its power.

In Maharashtra, shrikhand is the favorite. Strained yogurt, sweetened with sugar, and flavored with cardamom and saffron, it’s served chilled and often eaten with puris. It’s a post-meal palate cleanser, not a heavy dessert.

What Makes These Sweets ‘Traditional’?

Traditional Indian sweets aren’t just old-they’re made with ingredients and methods that haven’t changed much in 200 years. They rely on:

- Whole milk and dairy (khoya, chhena, rabri)

- Natural sweeteners like jaggery or raw sugar, not refined white sugar

- Spices like cardamom, saffron, nutmeg, and rose water

- Fermentation (for jalebi batter)

- Handmade shaping, not molds or machines

Modern versions use powdered milk, artificial colors, and preservatives-but the traditional ones don’t. That’s why you’ll find people in rural India still making jalebi batter at home, letting it sit overnight, then frying it fresh in the morning. The taste? It’s different. Deeper. Warmer. More alive.

How These Sweets Are Tied to Culture and Festivals

Indian sweets aren’t just food-they’re rituals. During Diwali, families make dozens of gulab jamun and ladoos to give as gifts. In South India, during Pongal, payasam is offered to the gods and then shared with neighbors. In Gujarat, during Navratri, people eat sweets made with jaggery instead of sugar as part of fasting traditions.

Even weddings follow a pattern: the bride’s family sends boxes of rasgulla to the groom’s family; the groom’s side replies with ladoos and barfi. The exchange isn’t just about taste-it’s about respect, abundance, and connection.

Some sweets are tied to specific communities. The Marwari community in Rajasthan prefers besan ladoo-made from roasted gram flour, ghee, and sugar. In Bengal, mishti doi (sweetened fermented yogurt) is a breakfast staple. In Tamil Nadu, pongal (a rice-and-milk dish sweetened with jaggery) is made during the harvest festival of the same name.

What You’ll Find in a Traditional Indian Sweet Shop

Step into a traditional Indian sweet shop, called a mithai ki dukaan, and you’ll see rows of sweets in metal trays, each labeled by name and price. The shopkeeper might be wearing a dhoti and a cap, and the air smells of ghee, cardamom, and caramelized sugar.

Here’s what you’ll typically find:

- Jalebi - Hot, crispy spirals in syrup

- Gulab jamun - Soft, fried milk balls in rose syrup

- Rasgulla - Spongy cheese balls in light syrup

- Ladoo - Round balls made from flour, gram, coconut, or besan

- Barfi - Dense, fudge-like squares made from milk solids

- Shrikhand - Thick, chilled yogurt dessert

- Payasam - Rice or vermicelli pudding in milk

- Mishti doi - Sweet fermented yogurt in earthen pots

Most shops make their sweets fresh daily. No preservatives. No freezers. If it’s not sold by evening, it’s thrown out. That’s tradition.

Why Modern Sweets Don’t Replace the Old Ones

You might think chocolate, ice cream, or cakes are taking over. But in India, they haven’t. Why? Because Indian sweets are tied to identity, not just taste. A child born in Chennai will eat payasam at their first birthday. A boy in Lucknow will get his first gulab jamun at Eid. A girl in Kolkata will have rasgulla at her college graduation.

Even in cities like Mumbai and Bangalore, where global desserts are everywhere, people still queue for hours for fresh jalebi. Why? Because it’s not just sugar-it’s memory. It’s the smell of frying batter on a cold morning. It’s the sound of syrup dripping into a metal tray. It’s the way your grandmother’s hands shaped each piece.

That’s why traditional Indian sweets endure. They’re not just desserts. They’re history on a plate.

What is the most popular traditional sweet in India?

Jalebi is the most widely recognized and consumed traditional sweet across India. Found in every state, it’s sold by street vendors, served at festivals, and eaten daily. While other sweets like gulab jamun and rasgulla are regionally dominant, jalebi’s universal appeal-crispy, syrupy, and affordable-makes it the closest thing to a national favorite.

Is jalebi the same as funnel cake?

No. While both are fried and syrup-coated, jalebi is made from a fermented batter of gram flour and water, giving it a unique tangy flavor and chewy texture. Funnel cake uses wheat flour and yeast, and is usually dusted with powdered sugar, not soaked in syrup. The fermentation process and the spiral shape are what make jalebi distinctly Indian.

Which Indian sweet is easiest to make at home?

Besan ladoo is one of the easiest. Just roast gram flour in ghee until fragrant, mix in sugar and cardamom, shape into balls, and let cool. No frying, no fermentation, no special equipment. It keeps for weeks and is perfect for beginners. Jalebi is trickier because the batter needs to ferment properly and the syrup must be at the right consistency.

Are traditional Indian sweets healthy?

Not really-they’re high in sugar and fat. But traditional versions use natural ingredients: jaggery instead of white sugar, ghee instead of vegetable oil, and whole milk. They don’t have preservatives or artificial flavors. Compared to modern cakes or cookies, they’re less processed. Still, they’re desserts, not health foods. Enjoy them in moderation.

Can I find traditional Indian sweets outside India?

Yes, but quality varies. In cities with large Indian communities-like London, New York, Toronto, or Sydney-you’ll find authentic sweet shops. Look for places that make sweets fresh daily and use terms like "handmade," "no preservatives," or "traditional recipe." Avoid supermarkets selling pre-packaged sweets-they’re often stiff, overly sweet, and lack the authentic texture.